United Through Arts celebrates Black History Month as we feature the achievements of the

Artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Archibald Motley

Born October 7, 1891, New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.—Died January 16, 1981, Chicago, Illinois

BIOGRAPHY

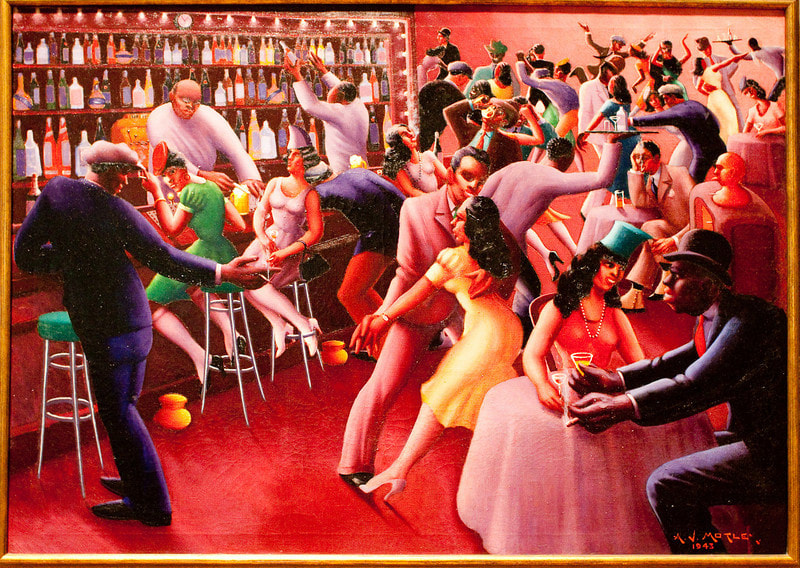

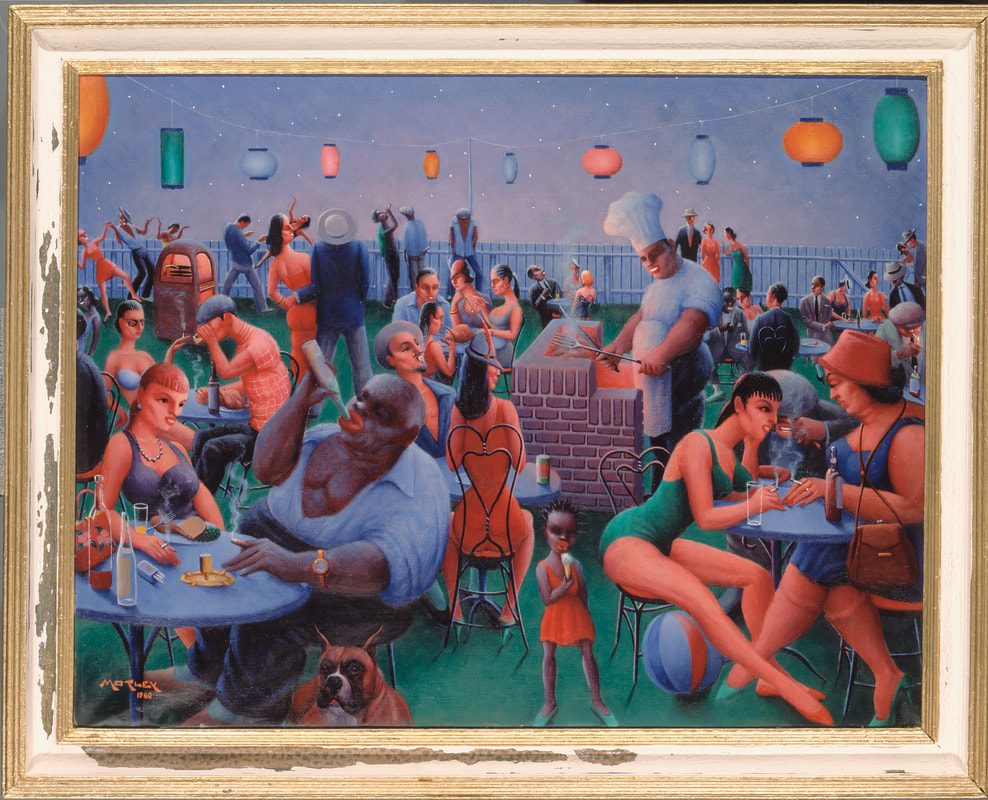

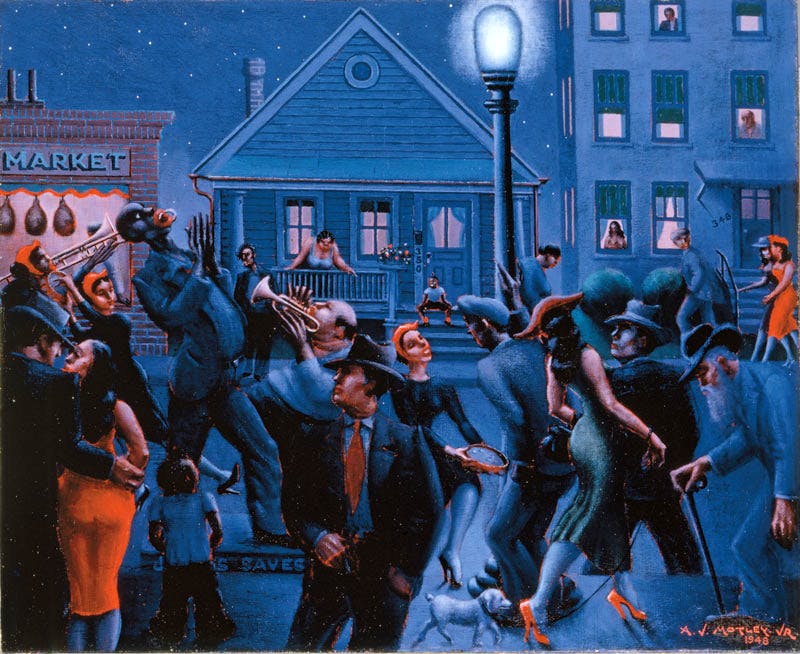

American painter identified with the Harlem Renaissance and probably best known for his depictions of black social life and jazz culture in vibrant city scenes.

When he was a young boy, Motley’s family moved from Louisiana and eventually settled in what was then the predominantly white neighborhood of Englewood on the southwest side of Chicago. His father found steady work on the Michigan Central Railroad as a Pullman porter. Though Motley received a full scholarship to study architecture at the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) and though his father had hoped that he would pursue a career in architecture, he applied to and was accepted at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied painting. In 1917, while still a student, Motley showed his work in the exhibition Paintings by Negro Artists held at a Chicago YMCA. That year he also worked with his father on the railroads and managed to fit in sketching while they traveled cross-country.

When he was a young boy, Motley’s family moved from Louisiana and eventually settled in what was then the predominantly white neighborhood of Englewood on the southwest side of Chicago. His father found steady work on the Michigan Central Railroad as a Pullman porter. Though Motley received a full scholarship to study architecture at the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) and though his father had hoped that he would pursue a career in architecture, he applied to and was accepted at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied painting. In 1917, while still a student, Motley showed his work in the exhibition Paintings by Negro Artists held at a Chicago YMCA. That year he also worked with his father on the railroads and managed to fit in sketching while they traveled cross-country.

Upon graduating from the Art Institute in 1918, Motley took odd jobs to support himself while he made art. An idealist, he was influenced by the writings of black reformer and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois and Harlem Renaissance leader Alain Locke and believed that art could help to end racial prejudice. At the same time, he recognized that African American artists were overlooked and undersupported, and he was compelled to write “The Negro in Art,” an essay on the limitations placed on black artists that was printed in the July 6, 1918, edition of the influential Chicago Defender, a newspaper by and for African Americans. The long and violent Chicago race riot of 1919, though it postdated his article, likely strengthened his convictions.

|

In the beginning of his career as an artist, Motley intended to solely pursue portrait painting. After graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1918, he decided that he would focus his art on black subjects and themes, ultimately as an effort to relieve racial tensions.

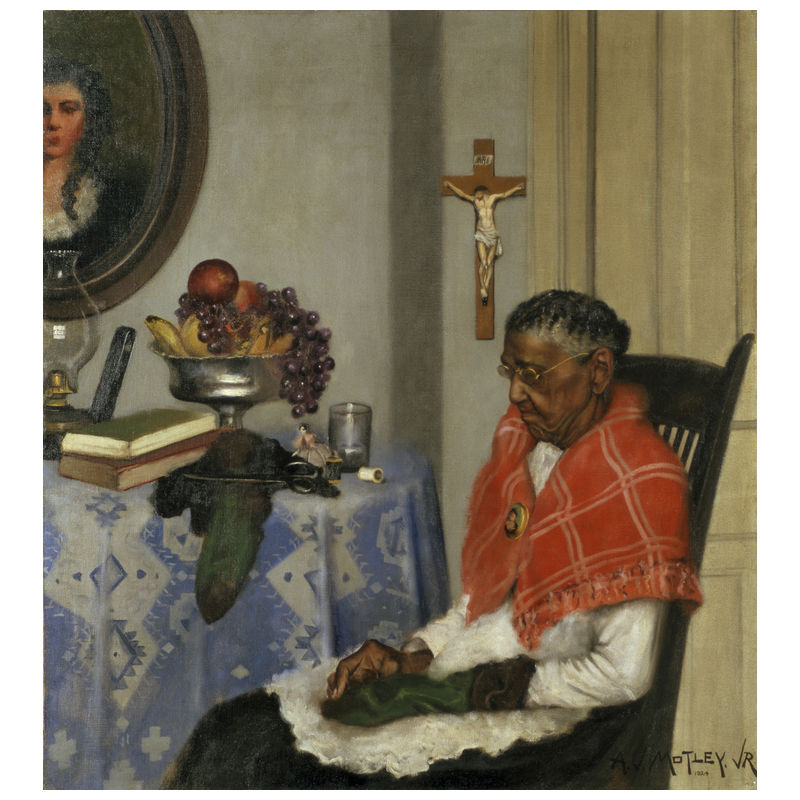

In 1919, Chicago's south side race riots rendered his family housebound for over six days. In the midst of this heightened racial tension, Motley was very aware of the clear boundaries and consequences that came along with race. He understood that he had certain educational and socioeconomic privileges, and thus, he made it his goal to use these advantages to uplift the black community. Motley experienced success early in his career; in 1927 his piece Mending Socks was voted the most popular painting at the Newark Museum in New Jersey. He was awarded the Harmon Foundation award in 1928, and then became the first African American to have a one-man exhibit in New York City. He sold 22 out of the 26 exhibited paintings. Motley would go on to become the first black artist to have a portrait of a black subject displayed at Chicago's Art Institute. |

Most of his popular portraiture was created during the mid 1920s. However, there was an evident artistic shift that occurred particularly in the 1930s. Motley strayed from the western artistic aesthetic, and began to portray more urban black settings with a very non-traditional aesthetic style. By breaking from the conceptualized structure of westernized portraiture, he began to depict what was essentially a reflection of an authentic black community. Ultimately, his portraiture was essential to his career in that it demonstrated the roots of his adopted educational ideals and privileges, which essentially gave him the template to be able to progress as an artist and aesthetic social advocate.

During the 1930s, Motley was employed by the federal Works Progress Administration to depict scenes from African-American history in a series of murals, some of which can be found at Nichols Middle School in Evanston, Illinois. After his wife's death in 1948 and difficult financial times, Motley was forced to seek work painting shower curtains for the Styletone Corporation. In the 1950s, he made several visits to Mexico and began painting Mexican life and landscapes.

|

|

His night scenes and crowd scenes, heavily influenced by jazz culture, are perhaps his most popular and most prolific. He depicted a vivid, urban black culture that bore little resemblance to the conventional and marginalizing rustic images of black Southerners so familiar in popular culture. It is important to note, however, that it was not his community he was representing—he was among the affluent and elite black community of Chicago. He married a white woman and lived in a white neighborhood, and was not a part of that urban experience in the same way his subjects were. |

In the 1920s and 1930s, during the New Negro Renaissance, Motley dedicated a series of portraits to types of Negroes. He focused mostly on women of mixed racial ancestry, and did numerous portraits documenting women of varying African-blood quantities ("octoroon," "quadroon," "mulatto"). In titling his pieces, Motley used these antebellum creole classifications ("mulatto," "octoroon," etc.) in order to show the social implications of the "one drop rule," and the dynamics of what it means to black.

He would expose these different "negro types" as a way to counter the fallacy of labeling all blacks as a generalized people. These direct visual reflections of status represented the broader social construction of blackness, and its impact on black relations. By asserting the individuality of African Americans in portraiture, Motley essentially demonstrated blackness as being "worthy of formal portrayal."

These portraits celebrate skin tone as something diverse, inclusive, and pluralistic. They also demonstrate an understanding that these categorizations become synonymous with public identity and influence one's opportunities in life. It is often difficult if not impossible to tell what kind of racial mixture the subject has without referring to the title. These physical markers of blackness, then, are unstable and unreliable, and Motley exposed that difference.

He would expose these different "negro types" as a way to counter the fallacy of labeling all blacks as a generalized people. These direct visual reflections of status represented the broader social construction of blackness, and its impact on black relations. By asserting the individuality of African Americans in portraiture, Motley essentially demonstrated blackness as being "worthy of formal portrayal."

These portraits celebrate skin tone as something diverse, inclusive, and pluralistic. They also demonstrate an understanding that these categorizations become synonymous with public identity and influence one's opportunities in life. It is often difficult if not impossible to tell what kind of racial mixture the subject has without referring to the title. These physical markers of blackness, then, are unstable and unreliable, and Motley exposed that difference.

By painting the differences in their skin tones, Motley is also attempting to bring out the differences in personality of his subjects. It could be interpreted that through this differentiating, Motley is asking white viewers not to lump all African Americans into the same category or stereotype, but to get to know each of them as individuals before making any judgments. In this way, his work used colorism and class as central mechanisms to subvert stereotypes. By harnessing the power of the individual, his work engendered positive propaganda that would incorporate "black participation in a larger national culture." Motley's work pushed the ideal of the multifariousness of blackness in a way that was widely aesthetically communicable and popular. In the end, this would instill a sense of personhood and individuality for blacks through the vehicle of visuality.